Australia’s international students remain firmly in the political and media firing line, regularly invoked in debates about population growth, housing shortages and pressure on services. Yet the latest overseas migration data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) suggests the reality is more complex than the dominant narrative allows.

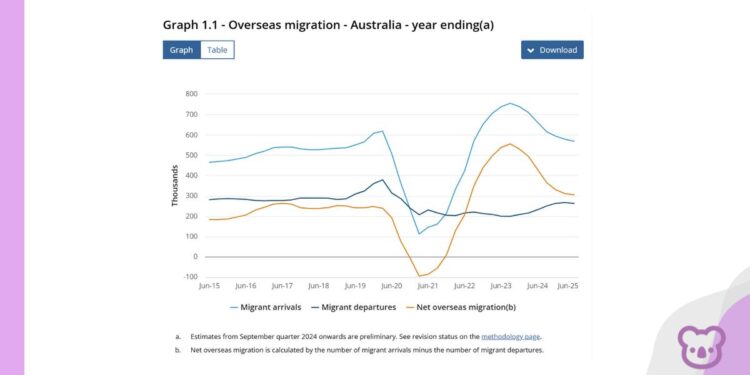

According to the ABS, net overseas migration (NOM) is easing after the sharp post-pandemic rebound that followed Australia’s border reopening. For the year ending June 2025, NOM fell again to an estimated 306,000 people, marking a second consecutive annual decline. That figure remains well above the levels assumed in recent federal budget forecasts, underscoring that migration pressures have not disappeared. However, the direction of travel is clearly downward, with departures increasing and overall population growth moderating from its post-pandemic peak.

International students continue to make up a substantial share of temporary arrivals. Around 157,000 student visa holders arrived during the period, accounting for close to half of all temporary entrants. That number is often cited in isolation. But migration outcomes are shaped not just by arrivals, but by how long people stay and how flows adjust over time.

While the ABS does not provide a visa-by-visa breakdown of departures, it shows that exits across temporary categories remain elevated compared with pre-pandemic norms. This reflects a migration system that is increasingly dynamic rather than one-way. Temporary migrants, including students, are not simply accumulating year on year in the way public debate often assumes.

Other indicators reinforce this picture. Student visa grant data shows that approvals have eased significantly from their post-pandemic highs, following a series of policy changes designed to tighten settings across the international education sector. Higher financial requirements, revised Genuine Student assessments, expanded integrity measures and closer scrutiny of providers and agents are all now flowing through to application and grant volumes.

This distinction is frequently lost in public discussion. International students are often treated as permanent additions to the population rather than as a highly mobile cohort whose numbers respond quickly to policy, cost-of-living pressures and global competition. The ABS data and visa trends together suggest that growth is no longer accelerating unchecked, even if overall migration remains historically high.

The Koala News has previously reported on the risks of collapsing a complex migration system into a single narrative that places international students at the centre of every pressure point. While housing affordability is undeniably strained in major cities, migration is only one factor among many. Long-term underinvestment in housing supply, planning constraints, construction delays and rising building costs have all played a central role.

Yet international students remain an easy target. They are visible, concentrated in inner-city locations and often lack a political voice. The result is a persistent framing of students as drivers of crisis rather than contributors to Australia’s economy, workforce and communities.

This is particularly striking given the policy environment students are already navigating. Over the past two years, international education has been subject to sustained regulatory tightening. The emerging data suggests these measures are having an effect, even if headline migration numbers remain higher than governments would prefer.

Despite this, international students continue to shoulder disproportionate blame. The tone of public debate risks undermining Australia’s reputation as a welcoming and stable study destination at a time when global competition for students is intensifying. Other major destinations are actively courting international students as future skilled workers, researchers and long-term economic contributors, while Australia’s domestic debate remains fixated on containment.

There is also a human dimension that is often overlooked. International students are not abstract figures in a migration ledger. They are young people navigating rising rents, limited housing availability and increasing living costs while balancing study, work and visa compliance. Repeatedly positioning them as a problem to be managed rather than participants in Australian society carries real consequences for wellbeing and belonging.

The latest ABS figures offer an opportunity to reset the conversation. Migration growth is moderating. Student demand is responding to policy and cost pressures. The system is adjusting, even if it has not yet returned to pre-pandemic settings assumed in budget forecasts. Continuing to single out international students as the primary source of pressure risks obscuring the broader structural challenges Australia needs to address.

If the data shows a more complicated picture, then the public debate should reflect that complexity. International students remain central to Australia’s education system, labour market and global engagement. Treating them as a convenient scapegoat may serve short-term politics, but it does little to support sound policy or Australia’s long-term interests.

As the Koala News has consistently argued, evidence should lead the conversation. The latest ABS data suggests it is time to move beyond blame and towards a more informed and proportionate discussion about migration, and the role international students actually play.

The ABS figures can be seen here.