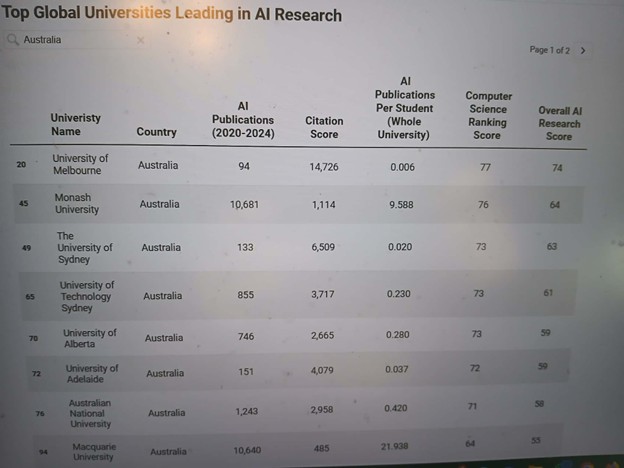

When the Koala-in-Chief shared the latest Studocu AI Research Survey results with me, I was delighted to see that, here in Australia, our universities appear to be punching well above their weight in global AI research. According to the survey, Australia ranked fourth in the world for AI-related research output—behind only the three research giants: the United States, China and the United Kingdom. Impressively, seven Australian universities made the global top-100 list.

As expected, the Group of Eight dominated the local landscape. Yet one of the survey’s more interesting findings was the limited correlation between research volume and research impact. Monash and Deakin, for example, produce large numbers of AI-related publications, yet fall behind the University of Melbourne in terms of their overall research influence.

While Studocu deserves genuine credit for the effort involved in identifying and analysing thousands of AI-themed publications—a monumental task in itself—the study is not without its limitations. One issue is the timeframe: the survey reviews publications from 2020 to 2024. Given the breakneck speed at which AI is evolving, research from 2020 may no longer reflect today’s technological reality. In 2020, unsupervised machine learning often counted as “AI”. Today, the frontier is dominated by large language models and human-AI collaboration.

Another concern raised by sceptics (and I reluctantly count myself among them) is the lack of clarity around the classification methods used to determine whether a publication was considered AI-related. With thousands of new papers published every month, manual review was impossible—but automated categorisation has its own pitfalls. AI research is famously interdisciplinary. A paper examining how AI is applied within a particular industry, for instance—was it classified as AI research or as industry research?

Adding to this, the study treats AI as a single umbrella category, despite the technology manifesting in countless forms. Lumping everything together may distort the accuracy of the rankings. It is also notable that the list of top AI-research universities does not differ substantially from traditional global rankings, such as those produced by Times Higher Education. While it is logical that leading institutions also lead in AI, the similarity raises questions about the objectivity of the methodology—and about how much the rankings truly reflect AI-specific excellence.

However, perhaps the more critical question lies elsewhere: even if Australia is performing strongly in AI research, are we meaningfully applying these insights in our own universities?

While we excel at researching AI, we lag significantly when it comes to deploying it across higher-education operations. My work modelling future AI-enabled universities may look futuristic, but wider adoption of AI across both academic and administrative processes is very much achievable today. And yet, paradoxically, our universities’ internal use of AI remains limited.

Currently, AI in Australian higher education is most commonly used for academic functions: content-similarity checks, assessment design, content production and similar tasks. Operational use remains sparse. Many university websites still lack AI chatbots capable of assisting users with navigation or answering common questions. Behind the scenes, the situation is not much better; compared with other sectors, universities have been slow to adopt AI-driven solutions that could streamline workflows, improve service delivery, or enhance efficiency.

Complicating matters further is an ongoing policy vacuum. TEQSA and other regulatory bodies have made efforts to develop guidelines for AI use in the post-secondary sector, but clear frameworks remain incomplete. Without them, universities face uncertainty about the extent to which they can—or should—transition to AI-supported or hybrid human-AI modes of operation. Similar gaps exist across many Australian industries that could benefit from adopting modern AI technologies more broadly.

Australia may be excelling in researching AI, but until our policies, practices and operations catch up, the full potential of this work will remain untapped. The question now is not whether our universities can lead in AI research—they already do—but whether they can embrace these same technologies in their own day-to-day operations.

Only then will the impact of all that excellent research truly be felt.